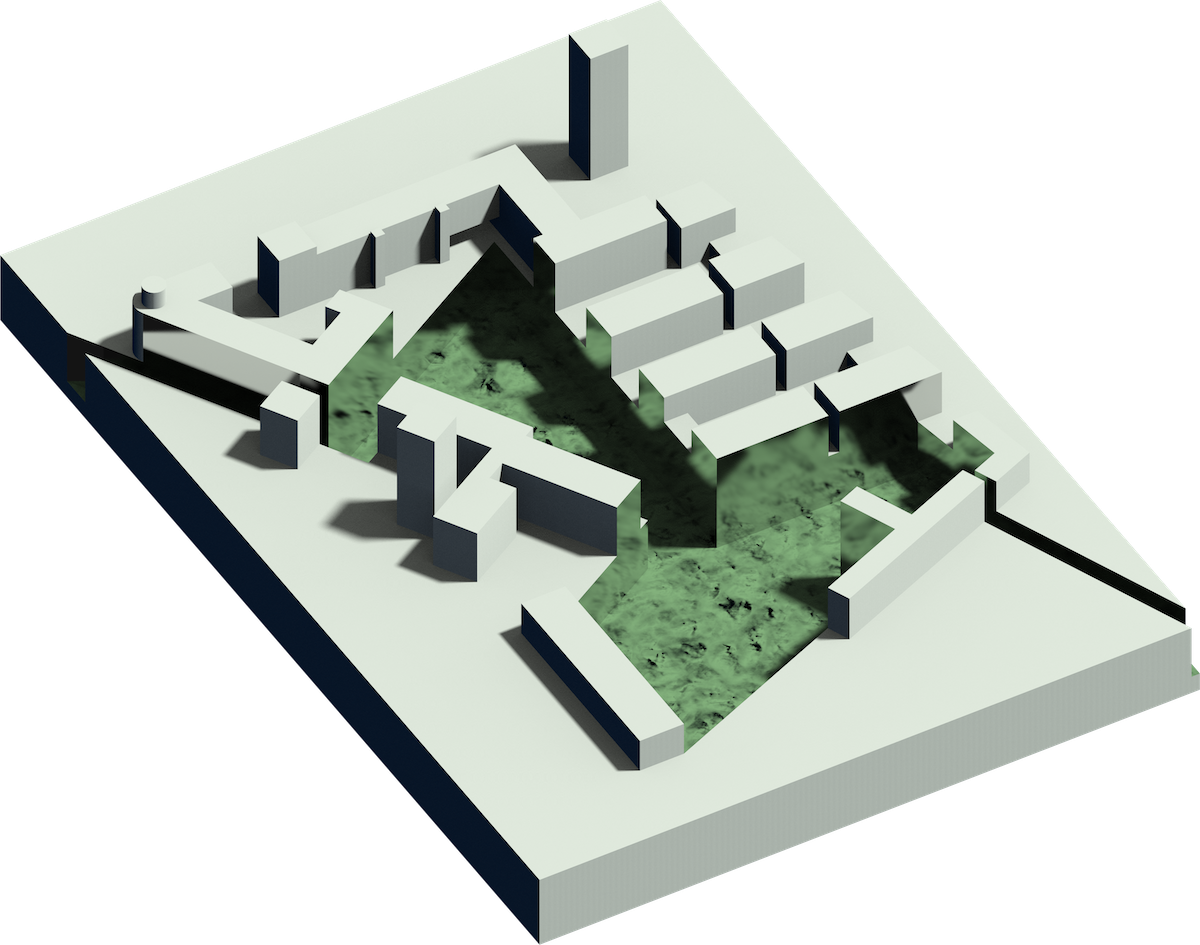

scheme 1

The first plan for the space created a small pocket of benignly neglected wilderness rather than a conventionally designed human-centric public park. The area between buildings surrounding the site is simply pushed into the ground, rendering it inaccessible for casual passersby. Canyons cut out into the surrounding landscape following the buried river. The decision to descend into the dense wetland that would develop would discourage casual use of the park as a thoroughfare while creating a rich experience for this who wish to be more fully immersed. The appearance of this site would be determined not through planning, but by the interaction of natural factors. This is not a park for people alone, but rather a small ecosystem of flora and fauna that people are required to approach with respect.

The walls of this downward extrusion would be clad in mirrored material, based on the substantial impact that the existing reflective apartment building facade has on the site’s sunlight coverage. This clearly imposing but starkly artificial boundary bypasses the issue of blocking, and neutrally takes on the existing shape of the site while suggesting infinite distance outward. The presence of surrounding buildings is not ignored, but rather merged into a unified boundary mass that shelters the park from the surrounding city.

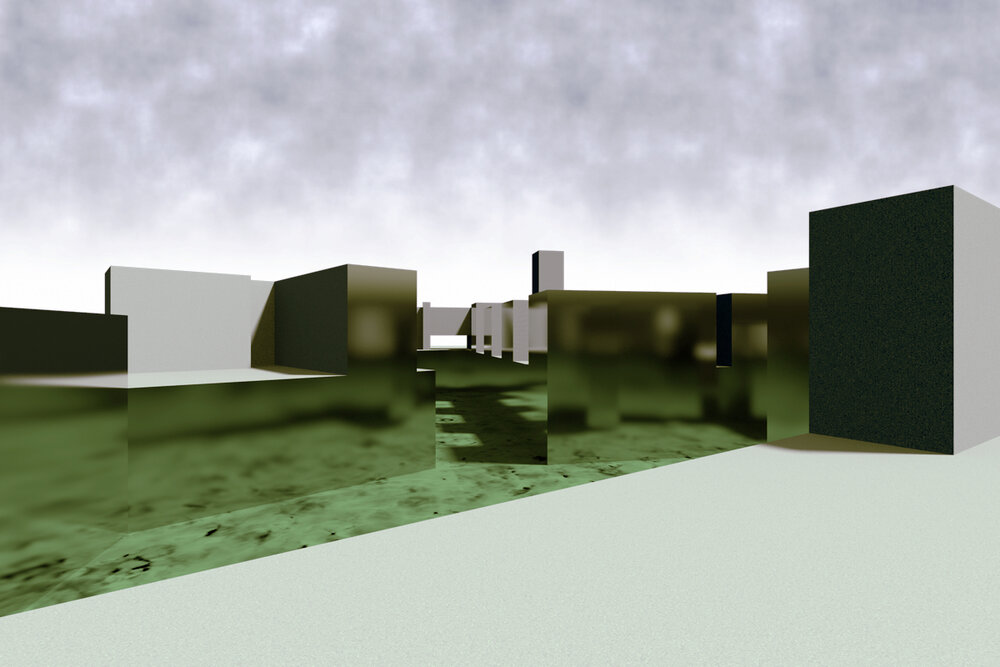

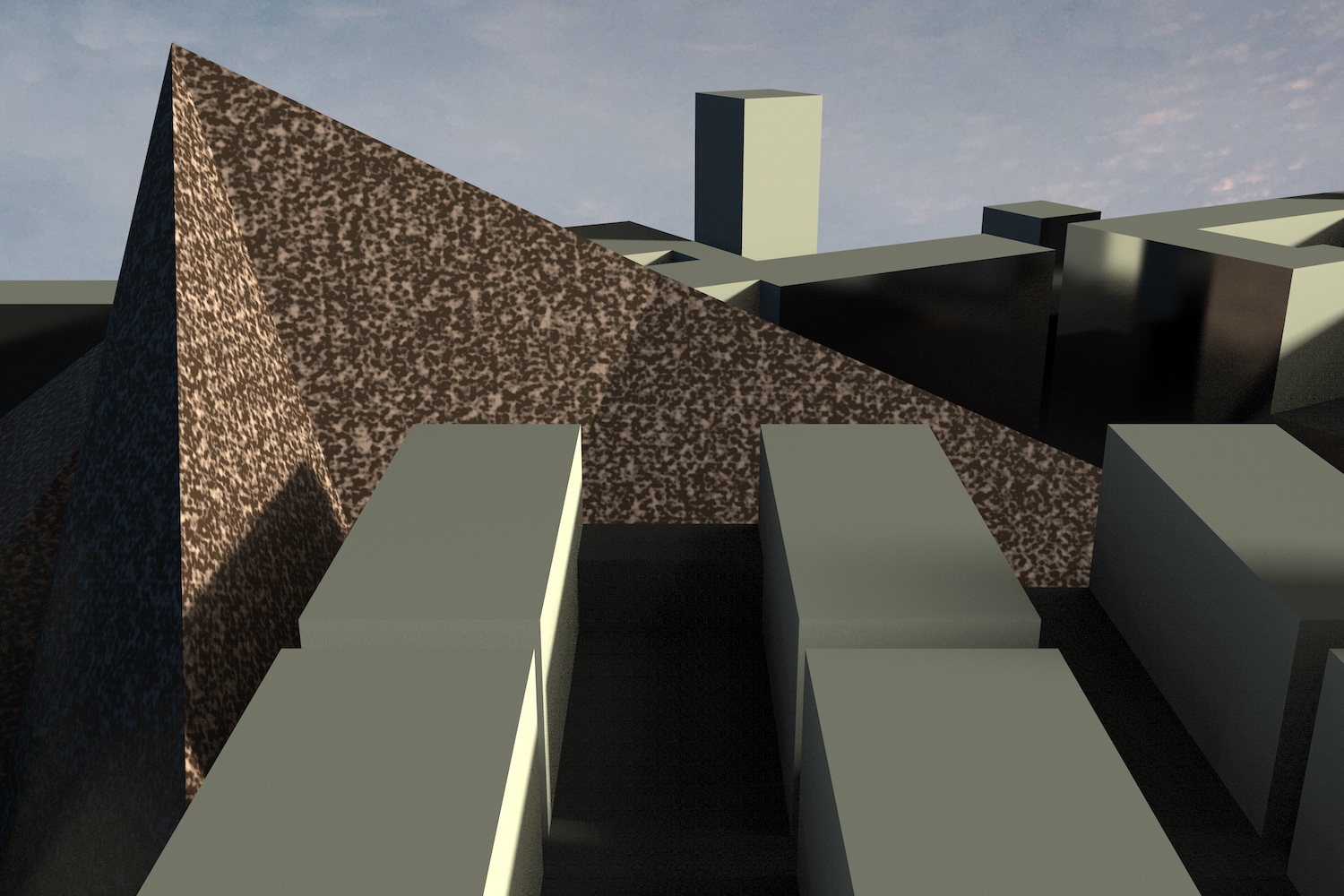

scheme 2

The second plan increases usable space at street level, connects more to adjacent buildings, and suggests open-ended categories for activities the park could potentially host. Each major new mass, or zone, in this plan references both an archetypal landscape feature and a type of movement. The multilevel design also responds to the Emmasingel site’s location, surrounded by many of the city’s taller buildings, while taking the form of the sort of intense geological landscape not found in the Netherlands.

The red Cave, a zone of acceleration

This subterranean area is located beneath the Mountain and the Plain, with a large ramp opening onto the existing plaza behind the Witte Dame building. The Cave, as an “underworld” and the most contained zone in the complex, plays host to typically repressed and regulated behaviours — a constant rave, carnival, or riot away from prying eyes. It may be partially observed through the opening but full immersion demands a symbolic descent.

The grey Mountain, a zone of stillness

The Mountain is physically elevated and unchanging, the antithesis of the Cave’s action and dynamism. It is a bare structure with the only real temporal variable being weather conditions, experienced here in a raw state. It is a publicly accessible link between the ground and the roofs of adjacent buildings, dissolving the social divide between residents and visitors.

The green Plain, a zone of growth

This is the most vegetated, conventionally park-like zone of the site. One area would serve as agricultural land according to permaculture principles, while other parts would simply be a grassy place to lay down on sunny day or play football. What goes on here can be expected to change cyclically with the seasons, while daily activities provide ever-changing colour.

The blue Canal, a zone of flow

While the city’s plan called for the buried river to be resurfaced, this implementation would cover much more surface area with water. The water is constantly replenishing itself while providing a fairly tranquil constant on the larger scale. Like the Plain, it is accessible for daily activities like swimming, fishing, or boating.

The seemingly distinct breaks between each zone should not be treated as such, and should furthermore be expected to dissolve with time as physical realities set in. The points where the zones meet should be somewhat unpredictable, with a tai chi class happening on the Mountain while a faint sound of tires squealing emanates from the Cave. The hope is that each group of people seeking out the park for different purposes is pushed into dialogue with other groups while still feeling comfortable with the familiarity of their surroundings. There is no attempt in this plan to create neutral ground. This will ideally emerge organically through negotiation and collaboration between people using the park at any given time.

Eindhoven’s Emmasingel area around the Witte Dame building in its historic capacity as a Philips complex

Designing a park landscape on a compressed scale is effectively an attempt to represent nature or some aspect of nature in a condensed, stylized manner that creates a sense of immersion. The landscape represented may be local, “exotic”, or generalized, with each of these aims having social or environmental consequences.

the local ecosystem

A park which responds to the local ecosystem starts with the current state of the site. Is it forest? Farmland? In the case of Emmasingel, the plot is postindustrial, with few embodied indications of the flora and fauna that would occupy the space absent human intervention. The river we know to be buried beneath the site is the key link back to an undeveloped state.

In Eindhoven’s wet climate, simply removing contaminated material, restoring the river, and limiting foot traffic could return the site to a natural state fairly quickly. However, remediating the plot without responding to the shape or constrained size of the area creates only a reduced version of the type of meadow that can be found outside the city. To address this, the landscape must be condensed and stylized in ways that expand the perceptual horizon.

usability

A balance must be determined between “real” nature and human accessibility as the landscape is more consciously altered. In areas without continuous human occupation, plant and animal life naturally moves in. Bruce Sterling talks about “involuntary parks” where ecosystems restore themselves after they become hostile to human use as a result of environmental or political shifts. Without active ecological aims, places like the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone and the Korean demilitarized zone have effectively become nature preserves comparable to intentionally preserved land.

The Emmasingel site is to be a city park, not a strict nature preserve, so the balance of functionality is expected to be tilted in favour of human occupants. Ground cover should accommodate circulation for people of all mobility levels, and the size of landscape features should be in some way reflective of human scale. The idea of cultivating a vibrant ecosystem with a hands-off approach can remain, however, in smaller-scale decisions. Cultivating native plant species, for instance, is an easy decision to benefit birds and insects native to the area, and designing the bank of the river as a soft rather than hard feature allows for flow between terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.

perceptual expansion

Aesthetic considerations come to the foreground when considering the feel of the park to someone passing through. With our relatively contained area, the illusion of space can be expanded by favouring wandering above rapid passing-through. In the American urban parks laid out by Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, time and space are effectively extended through routing of paths along indirect lines. This is paired with careful management of sight lines to minimize the presence of the surrounding built-up area, with open expanses generally located in lower areas bordered by tree-covered ridges.

The enclosed nature of the Emmasingel site means that these blocking strategies are not feasible for heightening immersion. A strategy of realistically-scaled, naturally-derived forms risks an outcome that feels inharmoniously truncated by extant hard architectural limits. A more explicitly artificial geometric landscape that leverages the existing edges and angles of the site can better address the existing lines of sight and movement out toward the larger city. The channelling of the river in and out of the park presents such an opportunity to cut into the surrounding streets, and at the same time introduce those exterior lines into the park.

open programming

It is in the interest of Design Academy students that the area's programming not become significantly more structured than it is now. Emmasingel in its current state is a transitional space that can be the location or subject of construction and performance experimentation. Too many divisions, obtrusive hard landscape features, and usage prescriptions would render the area too restrictive for freeform activities. Throughout the project, we have preferred to keep the intended uses of each part of the park as broad as possible to position the space in a responsive relationship to all its users. By leaving room for emergent behaviours, we increase the potential to improve the cultural and functional utility of the site in unforeseen ways.